Sometimes you wonder if you’re crazy. The older you get,

though, the easier it is to laugh at yourself. Old age. I can remember my paternal

grandmother, Clemmie Forrest Lewis (1902-1990), of Hudgins in

Mathews, making

jokes about craziness. When I was a little girl and she was my age, back in the

1960s when I was growing up in

Gloucester, she would cackle about someone doing

something worthy of being sent to “Dunbar” or, alternately, to “Williamsburg.”

It would be a while before I understood that this was a

reference to Eastern State, a hospital for the mentally ill, in Williamsburg, about

an hour’s drive from my childhood home. And Williamsburg is the town where I’ve

lived now for the last 40 years. In the 20th century, Dunbar was a farm about two miles

away where crops were raised to feed the patients and where some were sent for exercise

and rehabilitation. Beginning in 1936, as urged by the Williamsburg Restoration (later, Colonial Williamsburg), buildings were constructed at the farm and patients

were slowly, slowly shifted from the downtown Williamsburg location. In 1966,

there were still four patient buildings downtown. Finally, the last patients

were moved to the Dunbar Farms campus in 1970.

It would be a while before I understood that this was a

reference to Eastern State, a hospital for the mentally ill, in Williamsburg, about

an hour’s drive from my childhood home. And Williamsburg is the town where I’ve

lived now for the last 40 years. In the 20th century, Dunbar was a farm about two miles

away where crops were raised to feed the patients and where some were sent for exercise

and rehabilitation. Beginning in 1936, as urged by the Williamsburg Restoration (later, Colonial Williamsburg), buildings were constructed at the farm and patients

were slowly, slowly shifted from the downtown Williamsburg location. In 1966,

there were still four patient buildings downtown. Finally, the last patients

were moved to the Dunbar Farms campus in 1970.

My Nana must have had some real-life experience with mental

illness and Eastern State Hospital. Her husband, my grandfather, had three

aunts who were committed and died there. They probably weren’t the only people

from Mathews and Gloucester to be sent to “Williamsburg.” Why else would my

Sunday School class have been taken all the way to Eastern State Hospital (Dunbar

location) to sing carols at Christmas? I shiver. This memory is creepy . . . and

sad.

The Public Hospital for Persons of Insane and Disordered

Minds was established in 1770. It was a progressive move, yet the place was

referred to locally during the 18th and early 19th centuries as the asylum,

bedlam house, lunatic hospital, and madhouse. Not exactly politically correct,

by today’s standards. In 1861 the Public Hospital was renamed Eastern Lunatic

Asylum and in 1894 it was renamed again, Eastern State Hospital, since by that

time “lunatic” was generally recognized as having unkind overtones. For more on

the institution, read

Colonial Williamsburg’s research report that covers the

subject from the organization’s genesis in 1766 until a fire destroyed the original

colonial building and others in 1885.

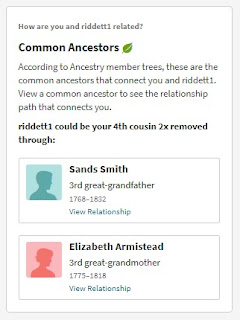

In addition to the three paternal-side aunts mentioned above,

I have another relative on my maternal side who was committed in 1880. Alice

Machen (1858-1918) was the sister-in-law of my 4th cousin, 3 times removed,

Willie Miller Machen (1859-1935). By the time Alice arrived at the age of 22,

Eastern Lunatic Asylum had undergone quite a bit of expansion after the Civil

War. Many new buildings made up the campus. The “female department” was located

in building C (see plan, right) and another female building, M, was completed in 1883.

Alice surely lived in one or both of these. Four years after she arrived, Consolidated

Electric Light installed electric lighting in the hospital buildings.

Five years after her committal, she may have been rescued

from building C, where a passerby saw flames leaping out of a window at 10:30 p.m.

In an account of the June 7, 1885 fire published two days later in the Richmond

Dispatch we learn:

“Dr. Moncure rushed through the

smoke, reached the room of the inmate nearest the fire, and picking her up in

his arms, carried her out to the veranda at the southeast angle of the building

and there turned her over to an employee. Quickly returning, he carried back

another, and his efforts were seconded by others, so that in a brief space of

time there were no inmates left in the immediate neighborhood of the fire.”

The females were taken to the “old College building” and “the

inmates in the male department had been turned out, and were straying around.” Since

there was no fire department in Williamsburg, an urgent message was sent to the

Richmond fire department, about 50 miles west. In the meantime, staff and

volunteers from town used hoses and wet blanket to fight the fire, until

someone suggested a portion of a building be blown up to stop the fire's advance

to the rest. It worked. In the end, the 1770 hospital building and four others (see plan: buildings A, C, D, E, and F) were destroyed and four (buildings I, L2, M, & N), possibly 5 (building J), survived.

The Richmond fire department arrived by train at 3 a.m., but it took several hours

to unload the horses and steam engine. They arrived in time to water down the

smoldering ruins. The hospital superintendent fed them breakfast and they were

back in Richmond by the afternoon.

Then, it was time to round up the patients, some of whom

were feared lost in the fire. It had been hard to keep the female patients from

wandering off, said one helper. They kept trying to find their way back to their

building. Finally, all were found, some taken in by kindly Williamsburg

residents. No lives were lost and the fire was blamed on the new electric

lights.

The hospital resumed operations on Francis Street, located one

block from, and parallel to, the Duke of Gloucester Street, which had been fashioned

nearly 200 years earlier as a grand one-mile-long avenue between The College of

William and Mary and Virginia’s colonial capitol building. After the American

Revolution, Virginia’s government offices moved from Williamsburg to Richmond, but

the Lunatic Asylum continued to serve those whom its founder, Virginia Governor

Fauquier, called the “poor unhappy set of People who are deprived of their

Senses and wander about the Country, terrifying the Rest of their Fellow

Creatures.” While Alice was a patient, Eastern State became Williamsburg’s

largest employer.

Alice died of tuberculosis in 1918, thirty-eight years after her

committal and at the age of 60. Her death certificate indicates that her parents’

names were unknown. Perhaps this key information had been lost in the fire? Or simply with time? Her

“occupation” at the institution was listed as “seamstress.” Alice also suffered

from pellagra, a condition caused by lack of niacin, related to a corn-heavy

diet and prevalent in the turn of the century South. Pellagra is said to be

characterized by the 4 Ds: diarrhea, dermatitis, dementia, and death. Because

of her length of stay at Eastern State, it is likely that Alice suffered from

some sort of mental disorder. The diseases followed, caused by lifestyle and

infection while she was a patient. She is most likely buried in an unmarked

grave in the Eastern State Cemetery on South Henry Street, now closed to

visitors, surrounded by an iron gate.

Although the hospital had no records of Alice’s family, I

know a bit about them due to that modern miracle: the Internet. Her father was

William Machen (1812-1879) whose first wife was Mary Fleet (Abt. 1820-Abt. 1850).

They lived with her parents, Henry and Elizabeth Fleet, a few houses away from

my second-great grandparents, Edmond and Harriet Jones of North who lived on Back Water

Creek. William was a ship joiner. The 1860 census finds him in Portsmouth, Virginia,

working as a carpenter and living with his second wife, who was half his age.

He must have been doing reasonably well because his real estate was valued at

$4,000 and his personal property at $5,000. Alice’s mother was Margaret R.

Snead (Abt. 1835-1900). The Portsmouth household included two sons by Mary Fleet,

ages 18 and 10, and two children by Margaret Snead, Charles, age 4, and little

Alice Machen, age 1. In 1870, after the Civil War, they were back in Mathews

where William was a farmer owning real estate valued at $2,500. Alice, Charles,

and one of their step-brothers made up the household. Among their neighbors were

the

Ruffs, mentioned in an earlier blog post, as well as another of my second-great

grandfathers, Joseph F. Foster, Sr. and his family.

William’s death in 1879 must have been a blow to the

household. The 1880 census finds Charles, age 24, farming, while his mother, 45,

is “housekeeping” and sister, Alice, 22, is “at home.” Margaret’s 50-year-old

sister-in-law also lived with them. Because Alice’s death certificate said she

had been at Eastern State for 38 years, she was probably committed sometime later

that census year. Also, according to marriage records, Charles Machen and my cousin, Willie Anne Miller. were married in December of 1880.

The 1890 U.S. Census records were nearly all destroyed in a

fire in 1921, so we don’t know what happened to Margaret Machen and her

sister-in-law during the last years of the Gilded Age. But the fin de siècle,

an age of rapid economic growth in America, was indeed the end of an era for

this family. In 1900, Margaret died, according to her obituary, “a widow lady .

. . at the home of her son, Mr. C. M. Machen, Forty-second Street” in Norfolk.

Just two months later, “Mr. Charles Machen, a resident of Lambert’s Point,”

died after a five-week illness. According to his obituary, “He belonged to a

very prominent family in Mathews county, and removed from there last Christmas.”

The 1900 census, taken in December, shows Charles’ wife, Willie, living in Norfolk

with seven children, ages 3 to 18. If she knew anything about her sister-in-law

Alice, she may have been too busy to be involved.

In 1926, less than ten years after Cousin Alice’s death and

before the arrival of the first of my three paternal aunts at Eastern State

Hospital, the Restoration of Williamsburg began. The Rector of Bruton Parish Church,

the Reverend Doctor W.A.R. Goodwin, brought the importance of the city to the

attention of Standard Oil tycoon John D. Rockefeller, Jr., who supplied funds

to launch the massive project. Located a block from Duke of Gloucester

Street, Eastern State was in the way.

According to a January 13, 1936 article in the Richmond

Times-Dispatch, “The hospitals have been overcrowded and in need of improvements

. . . for several years . . . The plan is to move eventually the whole hospital

from Williamsburg to the Dunbar farm . . .” The Rockefellers contributed $25,000

toward removal of the first unit “so the guests of the projected hotel may not

be disturbed by the cries of the louder patients.” The hotel, to be located

about a half mile away on Francis Street (The Williamsburg Inn), was needed to accommodate

the thousands of tourists visiting the restoration, they said. By 1940, four new

buildings were erected at Dunbar Farm, ready to house 500 people, less than

half of the patients.

The other state institution in downtown Williamsburg,

The College of William and Mary, wasn’t as eager to see the hospital move. Students

from William and Mary and other schools studied abnormal psychology and medical

law there. Students used a large hall at Eastern State for dances and hospital facilities

were also used for community concerts and events. In any case, World War II

interrupted progress on moving Eastern State as well as developments at Williamsburg

Restoration. It wasn’t until the 1950s that funds were budgeted by the state,

nudged by a generous Rockefeller incentive, and building began anew at Dunbar.

My paternal great grandmother, Elnora Davis Lewis (1860-1913),

was a contemporary of Alice Machen, although she was born on the other side of Mathews

County in the Piankatank District. She was the first child of Larkin Davis (About

1840-After 1877) and Sarah Elizabeth Winder (1835-1926). By 1870, the Davises

had three more children, two sons and another daughter, Ida Virginia, age 3. And

they were poor. Their real estate was valued at $100 and their personal

property at $100. By 1880, they had added another son and another daughter,

Sarah, age 3. The 1880 census also noted that Sarah, the mother, had

rheumatism. No one in the household could read or write. Elnora’s younger

siblings, Ida and Sarah, would spend their final days at Eastern State Hospital.

Great grandaunt Ida Virginia Davis (1869-1963) lived a long

life. She married Benjamin Franklin Thompson (1853-1946) and the couple had

three boys and two girls. At the age of 73, her youngest son, Ernest Jefferson

Thompson (1901-1942), was lost at sea off of Cape Hatteras when his merchant

ship, the SS Norvana, was torpedoed by a German submarine. A few years later,

in 1946 at the age of 77 and suffering from heart disease, Ida was committed to

Eastern State. Ida’s sibling, Sarah Elizabeth Davis (1877-1955) also lived a

long life before being taken to Eastern State in 1951. While Ida raised her

family in Mathews, Sarah moved in Norfolk with her first husband, Judson Hodges

(1877-1909), also of Mathews and captain of the tugboat Portsmouth. Not long after

moving, they had daughters, who were ages 2 and 3 when Judson died in Hampton

Roads harbor in a tugboat accident. Sarah remarried Marion Williams, a barge

captain, who moved into the Hodges home at 508 Poole Street, where they lived for

over 40 years. According to items in the newspaper social columns, Sarah took

trips back to Mathews frequently to visit her mother and siblings.

Also in the social pages, I found an interesting clip from

October 3, 1954. “Mrs. Luther F. Thompson, Mrs. William P. Lewis of Hallieford,

and A.L. Davis of Gloucester Point spent Friday in Williamsburg.” These were

the daughter-in-law and daughter of Ida and the brother of Ida and Sarah. I

wonder, were the women taking their uncle to visit Ida and Sarah? Were Ida and

Sarah at the downtown or Dunbar Farm campus of Eastern State? Did the visitors

take a stroll down the Duke of Gloucester Street, through Colonial Williamsburg,

while they were in town?

The Daily Press tells us that in 1953, “The Eastern

State Hospital is an overcrowded institution” with a rated capacity for 1,846

patients and 2,089 actual patients. “Even its four buildings erected at Dunbar

nearly two decades ago are 25% over capacity with 500 patients in quarters

provided for 400.” Another article in 1956 said that “aged women patients make

most of the hospital’s towels,” when reporting on progressive forms of therapy

at the institution. Overcrowding continued to be a hot topic in 1961 when the

newspaper headline proclaimed, “Eastern State Crowding: Problem is Aging.” One

third of the hospitals 2,400 patients were said to be elderly. “While Eastern

State is specifically intended to care for mental illness . . . , it . . . has

had to take on care of the aged . . . because the persons involved could not

afford private facilities . . .” Was Eastern State the best option for the

Davis sisters because they were aged, not mentally ill? Because Ida went into

the hospital first, did Sarah choose to be with her sister when she needed

additional care too?

Sarah died first, at the age of 77, after just 4 years, 2

months, and 13 days at the institution. According to her death certificate, she

died of lobar pneumonia in 1955. It is not clear why she was committed. Her

second husband, Marion, died two years after she was committed. The 1953 Norfolk

City Directory shows that Sarah and Judson Hodges's oldest daughter, Evelyn, and her

husband moved into

508 Poole Street, the home her parents made after moving from

Mathews more than 50 years earlier. He worked as an automobile salesman, a

cleaning and pressing business manager, and a mechanic. Sarah and Judson’s youngest

daughter, Lillian, also lived in Norfolk. Her Larchmont address and husband’s

career as a certified public accountant would lead one to believe she was better

off than her younger sister, yet for unknown reasons, her mother lived at

Eastern State. No judgement. Just saying.

Ida died in 1963 at the age of 94, after spending 17 years

at Eastern State. Earlier in life, between 1886 and 1901, she and husband Benjamin,

a farmer, had three sons and two daughters, four of whom were living when Ida

went to “Williamsburg” in 1946. First born Luther lived in Baltimore, Maryland,

where he enjoyed a career in the Merchant Marines. Daughter Ethel, 56, lived in

Halliford with her husband, a fisherman and chicken farmer, and two children. Daughter

Ruth, 51, lived with her family in Norfolk, where her husband was also a

Merchant Marine. Joseph, 47, lived near his parents in Mathews and worked for

the Colonial National Park in Yorktown. Although Ida had suffered from heart

disease for 30 years, her cause of death was listed as wasting disease, a

condition of wasting and weakening due to chronic illness.

Two years after Ida’s death, the last of my three paternal great

grandaunts, Clemmie Lewis Hunley (1874-1968), entered Eastern State. She also

lived a long life and was probably part of the third of Eastern State patients

who were aged and not mentally ill. She was the fifth of six children of

Robert T. Lewis (1828-1893) and Diannah Marchant (1837-1905) and the only girl.

She married Enos Littleberry Hundley in 1896 and their only child, Harold

Wainwright Hunley, was born two years later. Harold was another Merchant Marine.

He died in the U.S. Marine Hospital in Norfolk of sepsis in 1931. Clemmie lived

through many family tragedies. Her father died when she was 19 and Diannah

lived with Clemmie and Enos until her death in 1905, when Clemmie was 31. Her

brothers died in 1932, 1940, 1954, 1959, and 1964. The last brother died by suicide. Clemmie's husband, Enos, also died

in 1964, leaving Clemmie with no immediate family. They had not been well

off. In the 1940 U.S. Census, the last to be released (the National Archives

releases census records to the general public 72 years after the census date;

the 1950 census will be released in April 2022) Enos’s occupation is listed as

crabbing. I have no idea who, but someone in my extended family took Clemmie to

Eastern State, where she was admitted on June 14, 1965, and lived until she

died of a blessed heart attack in 1968, when she was 93.

About that time, entering my teenage years, I began my

special attraction to history. When I entered The College of William and Mary

in 1973, I was pleased to attend the historic college because I suspected that

some of my ancestors had attended the institution. I had no idea of my long family

connection to the other institution in town. Eastern State Hospital was by then tucked away on the old Dunbar farm.

Due to overcrowding at William and Mary, some of my fellow students lived in off-campus housing, about two miles away,

in leased buildings no longer used by Eastern State Hospital. The College named the annex James Blair Terrace and later the Dillard Complex. The JBT bus

rounded through William and Mary every few hours when I was a student.