In October 2020, I wrote a blog post about my black cousins.

I was casually scrolling through my

DNA matches, as defined by AncestryDNA,

and "discovered" that I had 25 Black cousins. And these were just the ones who had added

a photo to their Ancestry profile. This was at the same time surprising . . .

and not surprising. All but the poorest of my ancestors owned slaves, but

because I’m White, I’ve never had to think about the brutal reality of slave

life that has made the DNA of the average African American 25 percent European

American. Part of the brutal reality of White privilege is that I could remain “unawakened,”

while my Black cousins have been all too aware all along. Widespread sexual exploitation before the Civil War strongly influenced the genetic make-up of essentially all African Americans alive today.

In October 2020, I wrote a blog post about my black cousins.

I was casually scrolling through my

DNA matches, as defined by AncestryDNA,

and "discovered" that I had 25 Black cousins. And these were just the ones who had added

a photo to their Ancestry profile. This was at the same time surprising . . .

and not surprising. All but the poorest of my ancestors owned slaves, but

because I’m White, I’ve never had to think about the brutal reality of slave

life that has made the DNA of the average African American 25 percent European

American. Part of the brutal reality of White privilege is that I could remain “unawakened,”

while my Black cousins have been all too aware all along. Widespread sexual exploitation before the Civil War strongly influenced the genetic make-up of essentially all African Americans alive today.

Back in the fall, I compared myself with each of the 25 Black cousin to see the groupings of people AncestryDNA defined as our cousins, called “shared matches.” Ancestry analyzed and grouped each cousin and me with one to 30 other people who also took an AncestryDNA test. Shared match groups can discover others who share the same length and pattern of DNA, and therefore a common ancestor. (Of course, you can make as much or as little of your information public as you like.) My shared-match groupings include one to seven of my Black cousins with the rest being White cousins. I looked at the White cousins in each shared match grouping to see if we had a common ancestor – or simply other ancestors who might indicate a path back to Mathews, Virginia, or Old Bute County (Warren/Franklin/Granville), NorthCarolina.

I dug through the information for a while, even communicating with several Black cousins. They did not have any knowledge of ancestors in Mathews or Old Bute, although one traced an ancestor to King and Queen County. They expressed interest and hoped to learn something from my research. I also communicated with a White shared match in New York with documented ancestors from Kent, UK, but to no avail. I had a hunch that some Forrests were from Kent, but she had none with that surname. I filed my spreadsheets and let this project simmer.

A week or so ago I got another email from AncestryDNA, prodding me to check out the new cousins they had found for me. I scrolled through the list and saw three more Black cousins’ photos. I also did something I didn’t do the first time: I drilled down to the ethnicity percentages page of a dozen or more people who didn’t identify their race by posting a photo. Low and behold, I found many more Black cousins. So far, I’m up to 39 cousins of mixed African and European descent. When I get around to checking more ethnicity percentages, I bet I will find more.

I looked at all of the information posted by my two closest DNA cousins further, as well as Ancestry’s analysis and comparisons. These two cousins were the ones with the most matching DNA. They were even more closely related to me than Mercedes and Jonathan (shared DNA: 35 cM across 2 segments), who I identified as my top matches in October! Now I know that my closest Black cousin, Jackson (shared DNA: 116 cM across 5 segments), has a 77% chance of being my second cousin, or some other variation of half or “removed” 1st or 2nd cousin. She would have to fall in the half-cousin category, but anyway – Whoa. This means our shared ancestor could have been born after the Civil War. And then there is Wesley (shared DNA: 35 cM across 3 segments). He has a 58% chance of being in the third cousin ball park, which also means its possible our shared ancestors came of age after the Civil War. Both Jackson and Wesley posted family trees that hit close to my Mathews County home, including the surnames Lee, Jackson, Ruff, Borum, and Winder. Jackson’s ancestors were born in Mathews, while Wesley’s lived in Eastville, directly across the Chesapeake Bay from Westville, or Mathews.For most Black families, it’s difficult, if not impossible, to trace lineages back beyond the Civil War, when most of their ancestors were enslaved. According to her family tree and U.S. Census records, one of Jackson’s relatives, Thomas Lee, and his wife, Laura Wall, lived in the Piankatank District of Mathews in 1900. They had 10 children. Also in 1900, another ancestor, Andrew Jackson, lived in the Westville District with his wife, Betty Ruff, and 7 of their 12 children. Their tenth child, Harry Jackson, married Alice Borum.

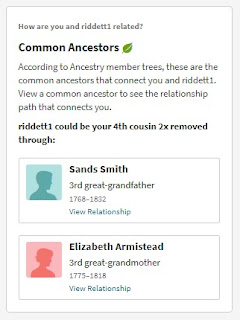

In the 1880 census, the distinction is made between Blacks and Mulattos, or people of mixed black and white parentage, a distinction that disappeared by the 1900 census. The word Mulatto originated with the degrading comparison of enslaved people to livestock: Horses and donkeys were different breeds and their offspring were mules, therefore the offspring of the White and Black races yielded “Mulattoes.” In 1880, the Andrew Jackson family, who lived on Whites Neck, had many Mulatto neighbors. Their surnames were Griffin, Ruff, Jones, Foster, Smith, White, Brooks, Hughes, Billups, Jarvis, and Weston. Since many enslaved people took the surnames of their former enslavers after the Civil War, it is possible that the White enslavers with these surnames were the fathers of Mulatto children. There is no clear line of relationship from Jackson to me, of course, but I had Jones, Foster, and other relatives in Westville who could be her half ancestors. Wesley’s and my shared match group includes Jackson. Of the 10 shared matches (one is me, one is my son, and one is Jackson), four of the seven remaining matches were other White folks who elected to share their family trees. I searched them for our shared ancestor. Unlike any of my other Black cousins in shared match groups, this relationship was clear. All four, like me, trace their ancestry to Sands Smith (1768-1832) and Elizabeth Armistead (1775-1818), who are my 3rd great grandparents. Descendants of Sands and Elizabeth Smith would be my 4th cousins or some variation of half or removed cousins below 4th. This does not mean that Sands is Wesley’s and my shared great-grandfather, but it does mean that Wesley and I are related due to the action of Sands, one of his brothers, or one of his or his brothers’ children . . . or Elizabeth’s father, one of his or Elizabeth’s brothers or one of these brothers’ children.I have more work to do to sort out my Black cousins. The 39 of them have been placed in one or more of 23 shared match groups with me. It's messy. Jackson is in three of the shared match groups and Wesley is in two groups. Jackson is only in one of Wesley's and my groups. So we have more than one shared ancestor. Across the groups, White shared matches who shared their family trees have in common with me ancestors with the surnames Smith, Armistead, Forrest, Marchant, Miller, Foster, Lewis, and Davis. Most of these White ancestors appear as the common ancestor in more than one group. Some groups have no named common ancestor. Only one shared match takes me to Old Bute County, North Carolina: back to a common 5th great grandmother, Elizabeth Bryant. I’m curious about one shared match group of 14 people: seven are White and seven have 50 percent or less DNA of African origin. There is no named common ancestor among the White people in this group.

Once again, this gives us something to think about. When you

visit or If you live in Mathews and you are descended from some of these

White ancestors, will this change how you look at the Black person, likely your

relative, you pass on the street? Or for the Black person who is reading this,

how will it change your view of the White people you pass? I hope more of my

Mathews people will take an AncestryDNA test to see how we are related and to help us home in on empathy and concern for

our true extended family.

No comments:

Post a Comment