Uncle Nathaniel is a most quintessential example of that Southern gentleman who would defend slavery to the end. It was this "uppity" white-gentry belief system that was behind the war before the war. Slavery as benevolent institution would become one of several tenets of Lost Cause mythology. I urge you to read War Before the War to learn more about that period of history we white people of a certain age didn't learn about when we were in school. We simply didn't bother to think about it either (Fiddle-de-dee, said Scarlet) because we grew up thinking that the Lost Cause was not a myth. Next, read Robert E. Lee and Me: A Southerner's Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause, for more on how General Jubal Early laid out the tenets of the Lost Cause Myth. This one is a must read. I'm about two-thirds through and haven't seen a relative . . . yet. Unless you count the loose reference to men like my 2nd great grandfather who was among the bedraggled who walked home from Petersburg rather than follow Lee to Appomattox.

Ancestor Confessions

Family history: slave traders, slave owners, slaves, and poor whites.

Wednesday, August 10, 2022

My Macon Ancestor's Irrational Rationalization is Quoted

Uncle Nathaniel is a most quintessential example of that Southern gentleman who would defend slavery to the end. It was this "uppity" white-gentry belief system that was behind the war before the war. Slavery as benevolent institution would become one of several tenets of Lost Cause mythology. I urge you to read War Before the War to learn more about that period of history we white people of a certain age didn't learn about when we were in school. We simply didn't bother to think about it either (Fiddle-de-dee, said Scarlet) because we grew up thinking that the Lost Cause was not a myth. Next, read Robert E. Lee and Me: A Southerner's Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause, for more on how General Jubal Early laid out the tenets of the Lost Cause Myth. This one is a must read. I'm about two-thirds through and haven't seen a relative . . . yet. Unless you count the loose reference to men like my 2nd great grandfather who was among the bedraggled who walked home from Petersburg rather than follow Lee to Appomattox.

Sunday, August 1, 2021

History Makes My Head Spin: From Manifest Destiny to King Offa

First, I had to do a quick study of the Santa Fe trail, reading what the National Park Service, Britannica, and other reliable sources had to say. Then I watched the 1940s Santa Fe Trail, a movie starring Errol Flynn, Olivia de Havilland and Ronald Reagan, and got hooked on watching all eight episodes of History on a Hog: Riding the Santa Fe Trail in Kansas: From it I got a better feel for the landscape, despite the sometimes-questionable interpretation of events.

Once I had a grip on the Santa Fe trail, I started to look for books about the California and Oregon trails to learn more about the direct ancestors of cousins I hardly know who chose to leave Virginia and North Carolina following the American Revolution. I selected the first library book that was available as an eBook at the moment: The Best Land Under Heaven: The Donner Party inthe Age of Manifest Destiny. While the idea of reading about cannibalism was off-putting, the idea of learning more about manifest destiny caught my attention. This is what America in the 19th century was all about.1846 Map. Library of Congress

The author states, “By 1845, the Reeds and Donners, like countless other Americans, generally accepted the idea that God had bestowed on the United States the right to grow and prosper by advancing the frontier westward. . . . Manifest Destiny became the nation’s watchword.” Although some, like Unitarian theologian William Ellery Channing disagreed – “We boast of our rapid growth, forgetting that, throughout nature, noble growths are slow . . . the Indians have melted before the white man, and the mixed degraded race of Mexico must melt before the Anglo-Saxon. . . . We talk of accomplishing our destiny. So did the late conqueror of Europe.” – but Channing was in the minority.

Politicians and religious leaders entwined their ideology to promote Manifest Destiny as a creation myth for the country. The author of the Donner Party book, written in 2017, perceived the origins of something many of us were startled to realize after the Unite the Right Rally in Charlottesville: “It soon became so ingrained in the national consciousness that many Americans still accept it to this day.” Yes, I see that now, not that all of the trailblazers were so passionate, but the concept of entitlement is deep-rooted. “The belief that God intended for the continent to be under the control of Christian European-Americans became official U.S. government policy. It helped to fuel incentive to take the land from those who were considered inferior to white Americans – indigenous tribal people characterized as savages and Mexicans, who were described as backward. In short, Manifest Destiny became a convenient way to . . . exterminate anyone who got in the way.”

Building Offa's Dyke, Pat Nicolle (1907-1995)I receive many enewsletters and Facebook posts from the UK due to my interest in my ancestral land. This morning I read a blog post about Offa, Anglo-Saxon King of Mercia. So, this made my head spin back in time to another drive that may have felt like destiny. Offa was an early Anglo Saxon who made war all around the island, exterminating anyone who got in the way of his power grab, and is promoted today as the first King of England. Since my DNA is more indigenous Briton than Anglo-Saxon, according to Ancestry, I celebrate that he was thwarted in his attempt to cross the line into the indigenous stronghold we know as Wales, the Land of My Fathers. Unfortunately, however, he forced the indigenous people to build a 150-mile-long dyke between the River Dee and the River Severn as a dividing line. Nevertheless, the Welsh people were eventually absorbed by the English about 500 years later. Is this the slow and noble growth that William Ellery Channing applauded?

People boil out of their kingdoms and some cannot be content. We are intentionally and unintentionally cruel and insensitive to those who are not us. Life makes my head spin.

Monday, April 12, 2021

At Appomattox, Mathews Men, including Robert T. Lewis, Fought to the (Near?) End

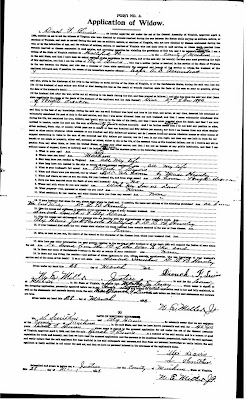

Twelve years after his death and two months before hers, on March 28, 1905, his widow and my 2nd great grandmother, Diana F. Marchant (1937-1905), filed a widow’s pension application, which was a benefit extended to Confederate widows by the United States government beginning in 1890. She said her husband served the Confederacy from "the 1st of the War to the end." She listed Leonard Smither and Alex Davis as comrades in arms with her husband.

Twelve years after his death and two months before hers, on March 28, 1905, his widow and my 2nd great grandmother, Diana F. Marchant (1937-1905), filed a widow’s pension application, which was a benefit extended to Confederate widows by the United States government beginning in 1890. She said her husband served the Confederacy from "the 1st of the War to the end." She listed Leonard Smither and Alex Davis as comrades in arms with her husband.

What made me think of the Surrender at Appomattox last week was Heather Cox Richardson’s April 8 “Letters from an American” newsletter in which she described the miserable conditions and, in the end, Grant’s actions, reflecting Lincoln’s “malice toward none; with charity for all” directive. Said Richardson in her newsletter, “Grant knew it was only a question of time before Lee had to surrender. The people in the Virginia countryside were starving and Lee’s army was melting away.” After the surrender papers were signed, Lee told Grant his men were starving and he asked the Union General for rations for the Confederate troops. Without missing a beat, Grant said yes, then asked how many men needed food. Lee answered, “about 25,000.” Not a problem. The Union had plenty.

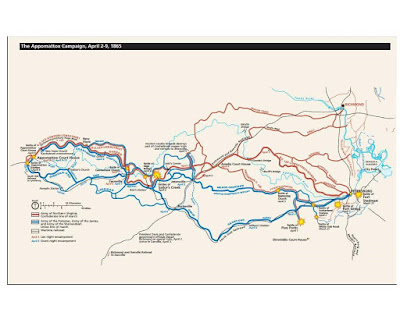

I had assumed Grandfather Robert was living in the midst of this horrific experience, but hadn’t looked into his service beyond the pension application, or examined his life around the time of the Civil War, until reading Richardson’s newsletter. This past weekend I began to research the details to relate as an Ancestor Confession. As I do in this blog, I write because I confess a family trespass or hardship or something I had not given much thought to before, in the spirit of my George Floyd-inspired awakening to racial injustice. In this case, I wondered, why did Robert T. Lewis serve from "the 1st of the War to the end?" I knew he wasn’t a wealthy slaveowner, like some of the Joneses, Smiths, and Billupses I researched and wrote about in March.On the National Park Service (NPS) web pages concerning the Civil War, Armistead’s Company, Virginia Light Artillery is described as “formed in July, 1861, with men from Mathews County. It first served at Yorktown.” In 1864, three years later, they fought “for some time” near Petersburg. Finally, they “surrendered with the Army of Northern Virginia” on April 9, 1865.

When organized, the unit contained 72 men. A local researcher noted that a total of 174 men are listed in records of the Mathews Light Artillery. Robert T. Lewis’s name appears in her list, as well as in the National Park Services’ list of Armistead’s Company, which includes 207 men. The NPS website also includes lists of prisoners of war taken at the Appomattox Court House surrender, and released with documentation, called parole passes, which allowed them to “return to their homes not to be disturbed by the United States Authority so long as they observed their parole and the laws in force where they reside.” On April 9, 1865, the Mathews Light Artillery unit contained 70 men who were taken prisoner and paroled.

My 2nd great grandfather was not among them. Neither was his comrade in arms Alex Davis. Leonard Smithers, however, served to the bitter end and received a prisoner of war’s parole pass.

I can certainly understand why my ancestor deserted, or simply didn’t make it to the Surrender due to the hardships of the Appomattox Campaign. The last record in his service file is dated 28 February 1865, according to Patrick Schroeder, historian, Appomattox Court House National Park. In an email message to me he continued, “What happened to him between the end of February and April 9, 1865, looks to be a mystery that may not be solved. More than 10,000 men left Lee’s army during the Appomattox campaign, so he may be one of those. Or perhaps he was sick and in a hospital somewhere.”Other essays on the NPS website describe the pre-surrender-year events. Beginning in the summer of 1864, Lee’s Army became trapped in Petersburg, Virginia, between Federal forces moving up from the south and Grant’s command to the north. By fall, three of the four railroads into Petersburg were severed. In the winter of 1864-1865, Lee recognized the danger posed by the armies closing in on him from the south and north. He wrote to the Confederate Secretary of War on February 8, 1865 that, “You must not be surprised if calamity befalls us.”

I wondered about the life circumstances leading up to my great great grandfather’s finding himself in this situation. I can’t find Robert T. Lewis in the 1850 U.S. Federal Census. But he was married to 18-year-old Diana Marchant on 6 Jan 1855 by Muse Hunley in her parent’s home. Curiously, five years earlier, the 1850 census does show a Walter Lewis, age 22, living with the Marchants when Diana was 13. Could the name Walter have been an error? Robert would have been 22 in 1850. Robert and Diana’s first son, my great grandfather, Charles Leonard Lewis (1855-1940), was born in December, 11 months after the couple’s marriage. In 1860, the Census finds them living next door to Diana’s recently widowed father, John J. Marchant (1806-1873), now with three sons. Her brother, John Wesley Marchant (1835-1886), his wife, and their two daughters lived with the senior Marchant, whose real estate was valued at $4,000, or about $127,000 today. Neither of his children’s families owned real estate, so it appears Robert, whose 1860 occupation was given as “Farmer,” farmed with his father-in-law, also a farmer. John Wesley’s occupation is listed as “Seaman.”

John J. Marchant’s name does not appear in the 1860 Census schedule as a slaveowner (nor does son-in-law Robert’s or son John’s), but that may be another error. He appeared as an enslaver of two people in 1850 and in 1860 a John H. Marchant appears to live in the neighborhood. He enslaved 13 people. Ten of them are spread between the ages of four months and 13 years. The other four are women, one aged 17 and the others in their 30s. If you believe that the Civil War was fought to maintain slave labor, this group seems out of keeping. The group is a mix of mostly dependent children. Ah, yes, but enslaved people were money, if he couldn't sell them to a neighbor, he sold to them to an itinerant slave trader who took them to the Richmond slave market.

Of course, the pragmatic notion that individuals would lose their personal free labor force had less to do with Virginians signing on as soldiers than the idea that they were protecting their collective property and security. Their shared sense of honor as a society, which practiced enslavement, was offended by the election of a Republican president hostile to slavery. Four years of war hardened their resolve. Confederates wanted separation from the Union as a matter of honor, but over time they grew to hate Northerners and see slavery as exceptionally important to their "honorable" way of life. Studies have shown that Virginia enlistment was highest in counties, not where the number of slaveholders was highest but where the percent of the population enslaved was the highest. The more people held as slaves, the higher the enlistment figures. About 45 percent of Mathews' population was enslaved. This says to me that my ancestors couldn’t imagine a community with Blacks living freely and equally among them. They could not concede to their agency as human beings.I looked through the lists of soldiers on the NPS website for

evidence of other ancestors at Appomattox. I found nothing, for now. In my last

post, I described another 2nd great grandfather’s experience. While Robert was bogged down in the Petersburg trenches, Walter Gabriel Jones was in prison at Point

Lookout, Maryland. I mentioned in the blog post that he was

“exchanged” on 16 March 1865. In reading about parole passes for this post, I

learned that the process of releasing prisoners of war may have also been referred

to as a parole or an exchange. So, Walter, with his official paperwork,

and Robert, who “disappeared” between February 28 and April 9, probably made it

back to Mathews at about the same time.

Another 2nd great grandfather, Joseph Finch Foster, Sr. (1819-1896), a slaveholder with real estate valued at $6,000, or just over $190,000 today, and personal property valued at $10,000, or about $317,000 today, was 46 years old in 1865. He did not serve in the Confederate military. However, he passed southeast of Petersburg, where Robert was entrenched, when traveling to Eagle Rock, Wake County, North Carolina, to marry his second wife Annie “Nannie” Glen Debnam (1835-1900) on 21 December 1864. She was the oldest daughter of Thomas Richard Debnam (1806-1873) and Priscilla Macon (1812-1878). In 1860, the Debnams owned 53 enslaved people.

In case you are interested in complicated genealogy, Richard and Pricilla Macon Debnam are my 3rd great grandparents, and parents of Annie “Nannie” Glen Debnam, mentioned above, and her sister of Arabella Catherine Debnam (1837-1900), who is my 2nd great grandmother and mother of my great grandmother Belle Catherine Hodge, second wife of Henry H. Foster (1851-1930). Other sisters of Nannie and Arabella were Madelaine and Corea. They were the first wives of Joseph Sr.’s sons, Henry H. Foster (1851-1930) and Joseph Jr. in 1870 and 1887. So, the Foster father and two of his sons married three Debnam sisters . . . and a niece. Henry was my great grandfather, Madelaine was his first wife, and Belle, the niece, was his second. But wait! There's more! Joseph Finch Foster, Sr.’s first wife, Anne Macon Hudgins (1830-1859) is my 2rd great grandmother. She is the daughter of my 3th great grandparents, Lewis Hudgins (1797-1866) and Elizabeth Williams (1804-1850). The Macon middle name suggests her mother Elizabeth Williams relates to Pricilla Macon somehow. Seriously, cousin marriages.

While researching and writing my Ancestor Confessions, I am learning a lot more than I first imagined. And knowledge is cumulative. I have unearthed relationships and connections I hadn’t known about. I see the past less as a foreign country. Personal history comes to life. Before, I hadn’t been a bit interested in the Civil War. In fact, I avoided everything to do with studying the Civil War and was angry about how many people seemed to celebrate the Lost Cause. But as I learn more about it now, I have greater empathy for my ancestors and their world. It dawned on me that there is injustice I need to take responsibility for, to repair. Perhaps this is one unconscious reason why I had not wished to examine the Civil War earlier, because of my implicit guilt.

Wednesday, March 31, 2021

Band of Brothers: Jones, Smith, and Billups

But perhaps the timing is right. These days I have the time and the will to confess my ancestors and, to paraphrase L.P. Hartley, process this foreign country that is my past.

After taking the sword home, I Googled until I decided it might be from the Civil War. By this time, my sister had found among my parents’ possessions some Confederate currency stashed between the pages of an old book. The plot had thickened. I gathered up a list of Confederate great grandfathers and took their records and the sword, which I didn’t know was actually a saber at the time, to my friend, J. Michael Moore, a Civil War historian.

Michael identified it as the kind of weapon a cavalryman used, while demonstrating how it might be wielded by a man on horseback. He thought the only one of my direct ancestors it could have belonged to was Walter Gabriel Jones (1837-1919). Because the saber had no makers' marks, Michael thought it was of the sort brought into the South from Europe by blockade runners. I was tempted to imagine that the saber was handed off to the young enlistee by my 3rd great grandfather Lewis Hudgins (1797-1866) who headed up a Mathews-based smuggling cartel that styled itself “the Arabs.”When he enlisted, great-grandfather Walter was 23 and lived with

his large family in the tall Federal-style house at North called “The Battery.”

The three-story house over a high English basement was built by his father,

Edmond Healy Jones (1798-1874), who came to Mathews from Middlesex and married

Harriet Smith (1809-1887) in 1827. Harriet’s brother was the locally renowned Sands Smith II (1803-1863).

By 1860, the year before the Civil War broke out, U.S. Census records say Edmond and Harriet Jones had seven sons and a daughter, ages seven to 30. The family lived on 337 acres and their real estate was valued at $10,000, or about $317,000 today. More than half of the property was wooded and 130 acres were “improved” or cultivated by the 15 people they enslaved. These people, whose names we will probably never know, lived in four cabins on the property. They grew wheat and corn, which were the most common crops grown in Mathews at that time. The Joneses also sold wood, possibly for shipbuilding.

Harriet’s older sister, Elizabeth Smith (1801-1870), got married a few years before her sister, in 1821. She married Robert Billups (1796-1872) and the Billupses and Joneses were neighbors on Blackwater Creek, a tributary of the North River. In 1860, they had two daughters and three sons, ages 19 to 28, living with them. Their oldest daughter, Sarah, had married Joshua Gayle, and the Gayles lived next door with five young children, ages two to 11. The Billupses' real estate (where the oldest son, Gaius, built Green Mansion in 1903) was valued at $20,000, or about $634,000 today. The 34 people they enslaved cultivated 320 of their 450 acres and were provided two cabins for all of them to live in, bunkhouse style.

On the other side of Mathews, Harriet’s brother, Sands, also lived on land valued at $10,000 in 1860. He and his wife had eight daughters, ages four to 24, and two sons, an infant and a nine-year-old. They enslaved 38 people who lived in four cabins on Smith’s plantation property called Beechland.

Another brother, Thomas Smith (1805-1880), lived near Sands at

Willow Grove, the house where the siblings’ parents had lived earlier. Harriet,

Elizabeth, Sands, and Thomas, as well as five more children of Sands Smith I

(1768-1832) and Elizabeth Armistead (1775-1818) were born there. Thomas had five

daughters, ages nine months to 24 years, and four sons, ages three to 20. His real

estate was also valued at $10,000. Thomas enslaved 54 people and provided five

cabins for their housing.

As a child, I never heard stories about the Civil War and slavery from family. A hundred years is a long time and most with first-hand knowledge were long gone, although I detected even then that some were sad or gruff for unknown reasons. I never knew about my maternal Jones family’s relation to the Smiths and the Billupses, either. However, what I did hear stories about was that the Joneses kept watch from the towering Battery’s attic windows for “enemies” coming from the lower Chesapeake Bay. As a child, I was unsure who those enemies might be, but it was an awesome and romantic tale.

What I’ve put together since is that the Jones-house-based watchers

were intent to aid their Smith family and friends on the other side of Mathews

during the Civil War. Confederate sympathizers all, they smuggled food, weapons, and supplies into the Chesapeake Bay and across from the Eastern

Shore. Smugglers tucked deep into Horn Harbor and other waterways. From Mathews’

docks, goods moved over land to wherever they were needed. Mathews was also the

source of direct food aid to the Confederacy, especially salt, milled grain,

and cattle.

What I’ve put together since is that the Jones-house-based watchers

were intent to aid their Smith family and friends on the other side of Mathews

during the Civil War. Confederate sympathizers all, they smuggled food, weapons, and supplies into the Chesapeake Bay and across from the Eastern

Shore. Smugglers tucked deep into Horn Harbor and other waterways. From Mathews’

docks, goods moved over land to wherever they were needed. Mathews was also the

source of direct food aid to the Confederacy, especially salt, milled grain,

and cattle.

Brothers Sands and Thomas Smith, like nearly everyone else in the county, were deeply sympathetic to and involved in smuggling activity. But the Union army was wise to them and determined to cut off the supply line through Mathews. This led to the deployment of 1,000 Federal troops and 11 gunboats, and a punishing counter-insurgent expedition known as Wister’s Raid.

Sixty-one-year-old Sands Smith, my second-great granduncle, is legendary for having shot a Union soldier and being dragged through Mathews in retaliation. He was then hanged, shot, and buried in a shallow grave as an example to other Mathews partisans. I don’t think this changed a single Mathews persons’ mind, though. They lionized Smith and dug their heels in further.My Jones, Smith, and Billups kin, like every person with a brain, had certain values at their core which were built and strengthened through life. They filtered new experiences through them and sprouted new brain wiring to support the core. They believed these learned and deeply rooted values, their way of life, prescribed the way things should be. Whether you believe in a cause for the Civil War that was right or wrong, this wired-in world view is why their young went to war. Their way of life was being challenged. You know, people just don’t like to be told what to do.

And their young men paid the price. In Mathews, the Confederacy’s first recruits, men ages 18 to 45, joined the Mathews Light Dragoons, F (3rd) Company, 5th Virginia Cavalry, on July 23, 1861. My great-grandfather was among them, as was his 28-year-old brother, Sands S. Jones (1833-1866), and his 20-year-old first cousin and next-door neighbor, Thomas G. Billups (1841-1886). Three more Jones brothers, Thomas (1829-1876), Lewis (1840-1904), and Christopher (1843-1919), and another first cousin and Thomas’s brother, Gaius W. Billups (1835-1920), also enlisted in the same cavalry unit by the summer of 1862. Of the Smiths, Sands had no sons of age to fight and Thomas had one, who joined an infantry unit, I believe (I haven't researched this fact thoroughly).

Of the four Smith siblings, Harriet, Elizabeth, Sands, and Thomas, my 2nd great grandmother, Harriet, had the most to grieve. Five sons left to fight for the Confederacy. Five sons! My heart aches and it brings me to tears to think about her living through all of this. The world was changing. Technological advances were making slavery less necessary, yet they couldn’t see a way forward. They couldn’t make their brains bypass the wiring that made them think their way of life was the way things were meant to be.

Of course, I never knew my great grandfather and his brothers. It would be interesting to interview them. Was war worth the costs? They certainly lost a lot. When my mother dug up a photo of my great grandparents Walter Gabriel Jones and Sarah Elizabeth Gayle, I remember my father saying they were “just poor dirt farmers,” or something of that sort. He didn’t know their history. Their world changed, a war was fought, they suffered, so it seems. Or perhaps not. Perhaps they were very happy with their lot. I will never know any more than what is intimated by the records I have found, and I share this below.

During the Civil War, 23-year-old Walter Jones fought in battles across Virginia for nearly two years until he was taken prisoner at Cold Harbor in the spring of 1864. At least he lived: of the 108,000 troops involved in the battle, nearly 15 percent lost their lives. It was also amazing that Walter survived yet another year at Point Lookout, a Union POW camp in Maryland, renowned as the worst and most crowded. According to the NationalPark Service website, Union prisons were filling up fast after the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863. Point Lookout’s POW population swelled from 1,700 to 9,000 in 1863. When Walter arrived in the summer of 1864, the prison population had grown to 15,500, well beyond the stockade’s capacity, and would reach 20,000 by the time all was said and done. Walter was “exchanged,” or sent back to his unit in exchange for Union POWs, on March 16, less than a month before the end of the war, on April 9, 1865. Prisoner exchanges were adopted during the Civil War to lessen the issues (overcrowding, lack of sanitation, disease) and costs associated with maintaining and moving captured soldiers.

Walter went home to Sarah Elizabeth Gayle (1844-1925), whom he had married in 1862, seemingly after his first year of battle and before reenlisting. After the war, on March 6, 1866, they welcomed their first child, Mollie. In 1868, Alice was born, and on March 4, 1870, Lewis was born. When 1870 census taker Owen stopped in, he recorded that the family was living in the Piankatank District of Mathews on 60 acres of land valued at $800, or about $16,000 today. They owned one horse, two milk cows, and a hog. During the previous year, they had grown 100 bushels of Indian corn and 50 bushels of oats.

[Interestingly—to me although not germane to this post—the next dwelling on the U.S. Census enumeration was occupied by paternal second great grandparents Absolom Forrest (1818-1871) and Columbia Ripley (b. 1836) and great grandfather Alpheons Lee “Allie” Forrest (1867-1949), then four years old. The Forrests lived on 11 acres valued at $300, or about $6,000 today.]

Thomas A. Jones (1829-1876), the oldest Jones brother, was 32 when he enlisted in August 1862. After a year and a half, he went AWOL (absent without leave) in November and December 1863. He had reasons to want to return to Mathews then: his mother, Harriet Smith, then in her 50s, had given birth to an eighth son, Henry C. Jones (1863-1946), her ninth and last child. Also, Mathews was the site of conflict from late summer into the fall. As mentioned above, Union troops were trying to halt Confederate smuggling operations and Sands Smith, Thomas’s uncle, was killed in October 1863. Despite the family emergency, Thomas was back with his unit in January 1864. In May 1864, he was one of 4,000 Confederate cavalrymen under General J.E.B. Stuart who met 12,000 Federal cavalrymen on their way to raid Richmond at Yellow Tavern. During the conflict that ensued, Stuart was shot and died the next day. Thomas was one of 300 cavalrymen who were captured and transferred to Fort Monroe in Hampton, then transferred to Point Lookout, Maryland. Although it was crowded, Thomas may have seen his brother there. Walter had been taken prisoner two weeks earlier. Thomas was transferred to the Union prison in Elmira, New York in August. Records say he escaped or was freed during a prisoner exchange, using an assumed name.After the war, Thomas returned to Mathews. The 1870 Census shows him occupied as a clerk and living with his parents, Edmond and Harriet Jones, and six siblings. War records list his death date as March 12, 1876, at the age of 46, just two years after the death of his father and 11 years before the death of his mother. He never married. The parents and son may be buried together at the Smith-Borum graveyard on Route 607 in Mathews, which served the homeplace at Willow Grove.

Sands S. Jones (1833-1866) was occupied as a seaman when he enlisted with Walter in July 1861. He was discharged from the cavalry unit for disability in June 1862. He died in 1866 at the age of 33. Unless a baby died in childbirth, which is entirely possible, Sands would be Edmond and Harriet’s first child to pass away. His place of burial is unknown, but it is likely he was buried in the family graveyard at Willow Grove with his martyred namesake uncle.

Lewis Robert Jones (1840-1904) enlisted in the 5th Virginia Cavalry with his brothers when he was about 21. He suffered a severe head wound in the Battle of the Wilderness, about a month before his brothers Walter and Thomas were taken as prisoners at Cold Harbor and Yellow Tavern. His situation after the war is unknown. A Civil War database says he died in King George County on May 3, 1904, and is buried in Mathews, although the location of his grave is also unknown. Since I suffered a head injury in a car crash when I was 21 and have studied neurology, I have an inkling of how his life may have unfolded. I have special empathy for him.

Christopher Muse Jones (1843-1919) was the youngest of the five Jones brothers who served in the 5th Virginia Cavalry. The Civil War database doesn’t give his age at enlistment, though he was possibly 18 or 19 years old, and there is no mention of him in available records of roll calls, battles, injury, or imprisonment. He is listed as living with his parents after the war, in the 1870 U.S. Census, but by the 1880 census he was living with his wife, Martha, and their three daughters in the Piankatank District of Mathews. The couple would have 11 children before he died in 1919.

After the Civil War, according to the 1870 census, Edmond and Harriet, ages 73 and 62, were living with Thomas (40), Christopher (23), “Doctor” (20), Mary E. (22), Ernest (17), and Henry (7). Their real estate was now valued at $7,000, or about $141,000 today, or half its worth ten years earlier. Walter was married and lived in the Piankatank District of Mathews. Sands was dead, and Lewis’s whereabouts are unknown. Between the Joneses and the next household of White people lived the Emancipated Black families of Daniel Parish, William Brown, Abraham Smith, and Charles Brucker. The Parish household included a 16-year-old girl named Sarah Jones.

After Harriet’s death in 1887, Walter and Sarah moved to the Battery with their ten children. The photo of Walter and Sarah that my father believed to represent “poor dirt farmers” must have been taken sometime before Walter’s death in 1919. Their son and my grandfather Roland Christopher Jones (1886-1963) married my grandmother, Laura Belle Foster (1890-1976) on October 21, 1915, and they moved into a house across North River Road from the Battery, where my mother was born.In the 1870 census enumeration, five households separated the Edmond Jones family from the brothers' first cousin and brother in arms, Thomas G. Billiups. In that year, he was 28 and a physician, living with his wife and children, ages one and three. His real estate was valued at $3,000, or about $60,000 today. His parents Robert (76) and Elizabeth (60) Billups, and sister, Roberta (26), live in the household, too.

If you are Black and you have read to the end of this post, you are certainly mocking the very idea that my family was sorely harmed by the Civil War. They were, but they weren’t. They didn’t know what it was like to suffer the pain and indignities of slavery, then a failed period of reconstruction and Jim Crow. And I don’t know what it’s like to live with systemic racism. I get it. I know.

No matter who you are, time marches on. We have history. We

learn lessons. How can a realistic look at our ancestors and their world help

us see each other more clearly? I am reminded of Tara Brach’s RAIN acronym. Rather

than continuing to believe that the way we see the world is the way it should

be, can we loosen our wiring long enough to recognize when we are being thrust

forward by impacted core beliefs? Can we accept that they are neither good nor

bad, that they are the result of time and experience? Can we investigate

how to get around being stuck in our worldview? Can we nurture a new path

forward?

Sunday, March 14, 2021

Finding More and Closer Black Cousins

In October 2020, I wrote a blog post about my black cousins.

I was casually scrolling through my

DNA matches, as defined by AncestryDNA,

and "discovered" that I had 25 Black cousins. And these were just the ones who had added

a photo to their Ancestry profile. This was at the same time surprising . . .

and not surprising. All but the poorest of my ancestors owned slaves, but

because I’m White, I’ve never had to think about the brutal reality of slave

life that has made the DNA of the average African American 25 percent European

American. Part of the brutal reality of White privilege is that I could remain “unawakened,”

while my Black cousins have been all too aware all along. Widespread sexual exploitation before the Civil War strongly influenced the genetic make-up of essentially all African Americans alive today.

In October 2020, I wrote a blog post about my black cousins.

I was casually scrolling through my

DNA matches, as defined by AncestryDNA,

and "discovered" that I had 25 Black cousins. And these were just the ones who had added

a photo to their Ancestry profile. This was at the same time surprising . . .

and not surprising. All but the poorest of my ancestors owned slaves, but

because I’m White, I’ve never had to think about the brutal reality of slave

life that has made the DNA of the average African American 25 percent European

American. Part of the brutal reality of White privilege is that I could remain “unawakened,”

while my Black cousins have been all too aware all along. Widespread sexual exploitation before the Civil War strongly influenced the genetic make-up of essentially all African Americans alive today.

Back in the fall, I compared myself with each of the 25 Black cousin to see the groupings of people AncestryDNA defined as our cousins, called “shared matches.” Ancestry analyzed and grouped each cousin and me with one to 30 other people who also took an AncestryDNA test. Shared match groups can discover others who share the same length and pattern of DNA, and therefore a common ancestor. (Of course, you can make as much or as little of your information public as you like.) My shared-match groupings include one to seven of my Black cousins with the rest being White cousins. I looked at the White cousins in each shared match grouping to see if we had a common ancestor – or simply other ancestors who might indicate a path back to Mathews, Virginia, or Old Bute County (Warren/Franklin/Granville), NorthCarolina.

I dug through the information for a while, even communicating with several Black cousins. They did not have any knowledge of ancestors in Mathews or Old Bute, although one traced an ancestor to King and Queen County. They expressed interest and hoped to learn something from my research. I also communicated with a White shared match in New York with documented ancestors from Kent, UK, but to no avail. I had a hunch that some Forrests were from Kent, but she had none with that surname. I filed my spreadsheets and let this project simmer.

A week or so ago I got another email from AncestryDNA, prodding me to check out the new cousins they had found for me. I scrolled through the list and saw three more Black cousins’ photos. I also did something I didn’t do the first time: I drilled down to the ethnicity percentages page of a dozen or more people who didn’t identify their race by posting a photo. Low and behold, I found many more Black cousins. So far, I’m up to 39 cousins of mixed African and European descent. When I get around to checking more ethnicity percentages, I bet I will find more.

I looked at all of the information posted by my two closest DNA cousins further, as well as Ancestry’s analysis and comparisons. These two cousins were the ones with the most matching DNA. They were even more closely related to me than Mercedes and Jonathan (shared DNA: 35 cM across 2 segments), who I identified as my top matches in October! Now I know that my closest Black cousin, Jackson (shared DNA: 116 cM across 5 segments), has a 77% chance of being my second cousin, or some other variation of half or “removed” 1st or 2nd cousin. She would have to fall in the half-cousin category, but anyway – Whoa. This means our shared ancestor could have been born after the Civil War. And then there is Wesley (shared DNA: 35 cM across 3 segments). He has a 58% chance of being in the third cousin ball park, which also means its possible our shared ancestors came of age after the Civil War. Both Jackson and Wesley posted family trees that hit close to my Mathews County home, including the surnames Lee, Jackson, Ruff, Borum, and Winder. Jackson’s ancestors were born in Mathews, while Wesley’s lived in Eastville, directly across the Chesapeake Bay from Westville, or Mathews.For most Black families, it’s difficult, if not impossible, to trace lineages back beyond the Civil War, when most of their ancestors were enslaved. According to her family tree and U.S. Census records, one of Jackson’s relatives, Thomas Lee, and his wife, Laura Wall, lived in the Piankatank District of Mathews in 1900. They had 10 children. Also in 1900, another ancestor, Andrew Jackson, lived in the Westville District with his wife, Betty Ruff, and 7 of their 12 children. Their tenth child, Harry Jackson, married Alice Borum.

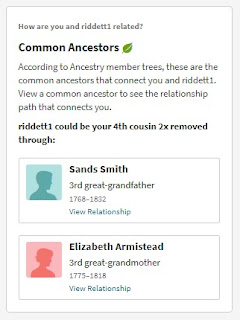

In the 1880 census, the distinction is made between Blacks and Mulattos, or people of mixed black and white parentage, a distinction that disappeared by the 1900 census. The word Mulatto originated with the degrading comparison of enslaved people to livestock: Horses and donkeys were different breeds and their offspring were mules, therefore the offspring of the White and Black races yielded “Mulattoes.” In 1880, the Andrew Jackson family, who lived on Whites Neck, had many Mulatto neighbors. Their surnames were Griffin, Ruff, Jones, Foster, Smith, White, Brooks, Hughes, Billups, Jarvis, and Weston. Since many enslaved people took the surnames of their former enslavers after the Civil War, it is possible that the White enslavers with these surnames were the fathers of Mulatto children. There is no clear line of relationship from Jackson to me, of course, but I had Jones, Foster, and other relatives in Westville who could be her half ancestors. Wesley’s and my shared match group includes Jackson. Of the 10 shared matches (one is me, one is my son, and one is Jackson), four of the seven remaining matches were other White folks who elected to share their family trees. I searched them for our shared ancestor. Unlike any of my other Black cousins in shared match groups, this relationship was clear. All four, like me, trace their ancestry to Sands Smith (1768-1832) and Elizabeth Armistead (1775-1818), who are my 3rd great grandparents. Descendants of Sands and Elizabeth Smith would be my 4th cousins or some variation of half or removed cousins below 4th. This does not mean that Sands is Wesley’s and my shared great-grandfather, but it does mean that Wesley and I are related due to the action of Sands, one of his brothers, or one of his or his brothers’ children . . . or Elizabeth’s father, one of his or Elizabeth’s brothers or one of these brothers’ children.I have more work to do to sort out my Black cousins. The 39 of them have been placed in one or more of 23 shared match groups with me. It's messy. Jackson is in three of the shared match groups and Wesley is in two groups. Jackson is only in one of Wesley's and my groups. So we have more than one shared ancestor. Across the groups, White shared matches who shared their family trees have in common with me ancestors with the surnames Smith, Armistead, Forrest, Marchant, Miller, Foster, Lewis, and Davis. Most of these White ancestors appear as the common ancestor in more than one group. Some groups have no named common ancestor. Only one shared match takes me to Old Bute County, North Carolina: back to a common 5th great grandmother, Elizabeth Bryant. I’m curious about one shared match group of 14 people: seven are White and seven have 50 percent or less DNA of African origin. There is no named common ancestor among the White people in this group.

Once again, this gives us something to think about. When you

visit or If you live in Mathews and you are descended from some of these

White ancestors, will this change how you look at the Black person, likely your

relative, you pass on the street? Or for the Black person who is reading this,

how will it change your view of the White people you pass? I hope more of my

Mathews people will take an AncestryDNA test to see how we are related and to help us home in on empathy and concern for

our true extended family.

Friday, February 26, 2021

Confessing My Eastern State Roots

It would be a while before I understood that this was a

reference to Eastern State, a hospital for the mentally ill, in Williamsburg, about

an hour’s drive from my childhood home. And Williamsburg is the town where I’ve

lived now for the last 40 years. In the 20th century, Dunbar was a farm about two miles

away where crops were raised to feed the patients and where some were sent for exercise

and rehabilitation. Beginning in 1936, as urged by the Williamsburg Restoration (later, Colonial Williamsburg), buildings were constructed at the farm and patients

were slowly, slowly shifted from the downtown Williamsburg location. In 1966,

there were still four patient buildings downtown. Finally, the last patients

were moved to the Dunbar Farms campus in 1970.

It would be a while before I understood that this was a

reference to Eastern State, a hospital for the mentally ill, in Williamsburg, about

an hour’s drive from my childhood home. And Williamsburg is the town where I’ve

lived now for the last 40 years. In the 20th century, Dunbar was a farm about two miles

away where crops were raised to feed the patients and where some were sent for exercise

and rehabilitation. Beginning in 1936, as urged by the Williamsburg Restoration (later, Colonial Williamsburg), buildings were constructed at the farm and patients

were slowly, slowly shifted from the downtown Williamsburg location. In 1966,

there were still four patient buildings downtown. Finally, the last patients

were moved to the Dunbar Farms campus in 1970.

My Nana must have had some real-life experience with mental

illness and Eastern State Hospital. Her husband, my grandfather, had three

aunts who were committed and died there. They probably weren’t the only people

from Mathews and Gloucester to be sent to “Williamsburg.” Why else would my

Sunday School class have been taken all the way to Eastern State Hospital (Dunbar

location) to sing carols at Christmas? I shiver. This memory is creepy . . . and

sad.

Five years after her committal, she may have been rescued

from building C, where a passerby saw flames leaping out of a window at 10:30 p.m.

In an account of the June 7, 1885 fire published two days later in the Richmond

Dispatch we learn:

“Dr. Moncure rushed through the

smoke, reached the room of the inmate nearest the fire, and picking her up in

his arms, carried her out to the veranda at the southeast angle of the building

and there turned her over to an employee. Quickly returning, he carried back

another, and his efforts were seconded by others, so that in a brief space of

time there were no inmates left in the immediate neighborhood of the fire.”

The females were taken to the “old College building” and “the

inmates in the male department had been turned out, and were straying around.” Since

there was no fire department in Williamsburg, an urgent message was sent to the

Richmond fire department, about 50 miles west. In the meantime, staff and

volunteers from town used hoses and wet blanket to fight the fire, until

someone suggested a portion of a building be blown up to stop the fire's advance

to the rest. It worked. In the end, the 1770 hospital building and four others (see plan: buildings A, C, D, E, and F) were destroyed and four (buildings I, L2, M, & N), possibly 5 (building J), survived.

The Richmond fire department arrived by train at 3 a.m., but it took several hours

to unload the horses and steam engine. They arrived in time to water down the

smoldering ruins. The hospital superintendent fed them breakfast and they were

back in Richmond by the afternoon.

Then, it was time to round up the patients, some of whom were feared lost in the fire. It had been hard to keep the female patients from wandering off, said one helper. They kept trying to find their way back to their building. Finally, all were found, some taken in by kindly Williamsburg residents. No lives were lost and the fire was blamed on the new electric lights.

The hospital resumed operations on Francis Street, located one block from, and parallel to, the Duke of Gloucester Street, which had been fashioned nearly 200 years earlier as a grand one-mile-long avenue between The College of William and Mary and Virginia’s colonial capitol building. After the American Revolution, Virginia’s government offices moved from Williamsburg to Richmond, but the Lunatic Asylum continued to serve those whom its founder, Virginia Governor Fauquier, called the “poor unhappy set of People who are deprived of their Senses and wander about the Country, terrifying the Rest of their Fellow Creatures.” While Alice was a patient, Eastern State became Williamsburg’s largest employer. Alice died of tuberculosis in 1918, thirty-eight years after her committal and at the age of 60. Her death certificate indicates that her parents’ names were unknown. Perhaps this key information had been lost in the fire? Or simply with time? Her “occupation” at the institution was listed as “seamstress.” Alice also suffered from pellagra, a condition caused by lack of niacin, related to a corn-heavy diet and prevalent in the turn of the century South. Pellagra is said to be characterized by the 4 Ds: diarrhea, dermatitis, dementia, and death. Because of her length of stay at Eastern State, it is likely that Alice suffered from some sort of mental disorder. The diseases followed, caused by lifestyle and infection while she was a patient. She is most likely buried in an unmarked grave in the Eastern State Cemetery on South Henry Street, now closed to visitors, surrounded by an iron gate. Although the hospital had no records of Alice’s family, I know a bit about them due to that modern miracle: the Internet. Her father was William Machen (1812-1879) whose first wife was Mary Fleet (Abt. 1820-Abt. 1850). They lived with her parents, Henry and Elizabeth Fleet, a few houses away from my second-great grandparents, Edmond and Harriet Jones of North who lived on Back Water Creek. William was a ship joiner. The 1860 census finds him in Portsmouth, Virginia, working as a carpenter and living with his second wife, who was half his age. He must have been doing reasonably well because his real estate was valued at $4,000 and his personal property at $5,000. Alice’s mother was Margaret R. Snead (Abt. 1835-1900). The Portsmouth household included two sons by Mary Fleet, ages 18 and 10, and two children by Margaret Snead, Charles, age 4, and little Alice Machen, age 1. In 1870, after the Civil War, they were back in Mathews where William was a farmer owning real estate valued at $2,500. Alice, Charles, and one of their step-brothers made up the household. Among their neighbors were the Ruffs, mentioned in an earlier blog post, as well as another of my second-great grandfathers, Joseph F. Foster, Sr. and his family.William’s death in 1879 must have been a blow to the household. The 1880 census finds Charles, age 24, farming, while his mother, 45, is “housekeeping” and sister, Alice, 22, is “at home.” Margaret’s 50-year-old sister-in-law also lived with them. Because Alice’s death certificate said she had been at Eastern State for 38 years, she was probably committed sometime later that census year. Also, according to marriage records, Charles Machen and my cousin, Willie Anne Miller. were married in December of 1880.

The 1890 U.S. Census records were nearly all destroyed in a fire in 1921, so we don’t know what happened to Margaret Machen and her sister-in-law during the last years of the Gilded Age. But the fin de siècle, an age of rapid economic growth in America, was indeed the end of an era for this family. In 1900, Margaret died, according to her obituary, “a widow lady . . . at the home of her son, Mr. C. M. Machen, Forty-second Street” in Norfolk. Just two months later, “Mr. Charles Machen, a resident of Lambert’s Point,” died after a five-week illness. According to his obituary, “He belonged to a very prominent family in Mathews county, and removed from there last Christmas.” The 1900 census, taken in December, shows Charles’ wife, Willie, living in Norfolk with seven children, ages 3 to 18. If she knew anything about her sister-in-law Alice, she may have been too busy to be involved.

In 1926, less than ten years after Cousin Alice’s death and before the arrival of the first of my three paternal aunts at Eastern State Hospital, the Restoration of Williamsburg began. The Rector of Bruton Parish Church, the Reverend Doctor W.A.R. Goodwin, brought the importance of the city to the attention of Standard Oil tycoon John D. Rockefeller, Jr., who supplied funds to launch the massive project. Located a block from Duke of Gloucester Street, Eastern State was in the way.According to a January 13, 1936 article in the Richmond Times-Dispatch, “The hospitals have been overcrowded and in need of improvements . . . for several years . . . The plan is to move eventually the whole hospital from Williamsburg to the Dunbar farm . . .” The Rockefellers contributed $25,000 toward removal of the first unit “so the guests of the projected hotel may not be disturbed by the cries of the louder patients.” The hotel, to be located about a half mile away on Francis Street (The Williamsburg Inn), was needed to accommodate the thousands of tourists visiting the restoration, they said. By 1940, four new buildings were erected at Dunbar Farm, ready to house 500 people, less than half of the patients.

The other state institution in downtown Williamsburg, The College of William and Mary, wasn’t as eager to see the hospital move. Students from William and Mary and other schools studied abnormal psychology and medical law there. Students used a large hall at Eastern State for dances and hospital facilities were also used for community concerts and events. In any case, World War II interrupted progress on moving Eastern State as well as developments at Williamsburg Restoration. It wasn’t until the 1950s that funds were budgeted by the state, nudged by a generous Rockefeller incentive, and building began anew at Dunbar.My paternal great grandmother, Elnora Davis Lewis (1860-1913), was a contemporary of Alice Machen, although she was born on the other side of Mathews County in the Piankatank District. She was the first child of Larkin Davis (About 1840-After 1877) and Sarah Elizabeth Winder (1835-1926). By 1870, the Davises had three more children, two sons and another daughter, Ida Virginia, age 3. And they were poor. Their real estate was valued at $100 and their personal property at $100. By 1880, they had added another son and another daughter, Sarah, age 3. The 1880 census also noted that Sarah, the mother, had rheumatism. No one in the household could read or write. Elnora’s younger siblings, Ida and Sarah, would spend their final days at Eastern State Hospital.

Great grandaunt Ida Virginia Davis (1869-1963) lived a long life. She married Benjamin Franklin Thompson (1853-1946) and the couple had three boys and two girls. At the age of 73, her youngest son, Ernest Jefferson Thompson (1901-1942), was lost at sea off of Cape Hatteras when his merchant ship, the SS Norvana, was torpedoed by a German submarine. A few years later, in 1946 at the age of 77 and suffering from heart disease, Ida was committed to Eastern State. Ida’s sibling, Sarah Elizabeth Davis (1877-1955) also lived a long life before being taken to Eastern State in 1951. While Ida raised her family in Mathews, Sarah moved in Norfolk with her first husband, Judson Hodges (1877-1909), also of Mathews and captain of the tugboat Portsmouth. Not long after moving, they had daughters, who were ages 2 and 3 when Judson died in Hampton Roads harbor in a tugboat accident. Sarah remarried Marion Williams, a barge captain, who moved into the Hodges home at 508 Poole Street, where they lived for over 40 years. According to items in the newspaper social columns, Sarah took trips back to Mathews frequently to visit her mother and siblings.The Daily Press tells us that in 1953, “The Eastern State Hospital is an overcrowded institution” with a rated capacity for 1,846 patients and 2,089 actual patients. “Even its four buildings erected at Dunbar nearly two decades ago are 25% over capacity with 500 patients in quarters provided for 400.” Another article in 1956 said that “aged women patients make most of the hospital’s towels,” when reporting on progressive forms of therapy at the institution. Overcrowding continued to be a hot topic in 1961 when the newspaper headline proclaimed, “Eastern State Crowding: Problem is Aging.” One third of the hospitals 2,400 patients were said to be elderly. “While Eastern State is specifically intended to care for mental illness . . . , it . . . has had to take on care of the aged . . . because the persons involved could not afford private facilities . . .” Was Eastern State the best option for the Davis sisters because they were aged, not mentally ill? Because Ida went into the hospital first, did Sarah choose to be with her sister when she needed additional care too?

Sarah died first, at the age of 77, after just 4 years, 2 months, and 13 days at the institution. According to her death certificate, she died of lobar pneumonia in 1955. It is not clear why she was committed. Her second husband, Marion, died two years after she was committed. The 1953 Norfolk City Directory shows that Sarah and Judson Hodges's oldest daughter, Evelyn, and her husband moved into 508 Poole Street, the home her parents made after moving from Mathews more than 50 years earlier. He worked as an automobile salesman, a cleaning and pressing business manager, and a mechanic. Sarah and Judson’s youngest daughter, Lillian, also lived in Norfolk. Her Larchmont address and husband’s career as a certified public accountant would lead one to believe she was better off than her younger sister, yet for unknown reasons, her mother lived at Eastern State. No judgement. Just saying.Ida died in 1963 at the age of 94, after spending 17 years

at Eastern State. Earlier in life, between 1886 and 1901, she and husband Benjamin,

a farmer, had three sons and two daughters, four of whom were living when Ida

went to “Williamsburg” in 1946. First born Luther lived in Baltimore, Maryland,

where he enjoyed a career in the Merchant Marines. Daughter Ethel, 56, lived in

Halliford with her husband, a fisherman and chicken farmer, and two children. Daughter

Ruth, 51, lived with her family in Norfolk, where her husband was also a

Merchant Marine. Joseph, 47, lived near his parents in Mathews and worked for

the Colonial National Park in Yorktown. Although Ida had suffered from heart

disease for 30 years, her cause of death was listed as wasting disease, a

condition of wasting and weakening due to chronic illness.

My Macon Ancestor's Irrational Rationalization is Quoted

It is a bit startling to run across your ancestor's name in a well-regarded book on the topic of race and slavery. Well, I suppose I sho...

-

While cleaning out my parents’ house last year, my sister found an old sword tucked in a back corner of the foyer closet. We were surprised ...

-

Ancestry estimated my ethnicity and told me I had more than a thousand 4th cousins or closer relatives who had also sent DNA samples for ana...

-

Last Friday, April 9, was the 156 anniversary of Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s surrender to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomatt...