My grandmother, Laura Belle Foster (1890-1976), thought the world of her little brother, my Uncle Howitt (Howitt Hodge Foster, M.D., 1893-1980). He was the last child of great grandfather Henry Howitt Foster (1851-1930), who had eight children with his first wife, Madeline Debnam (1850-1885), and three with his second wife and my great grandmother, Belle Catherine Hodge (1863-1893). You may have noticed that Great Grandmother Belle died in the year Uncle Howitt was born. Since his father, Henry, was 42 years old with ten other children to feed and a business to run in Mathews, Virginia, baby Howitt was sent to live with Belle’s parents in Wake County, North Carolina. There Howitt grew up with his grandparents and then his Aunt Fannie. He became a doctor like Fannie’s husband John Smith, and practiced family medicine in Norlina, North Carolina, for the rest of his life.

Like my grandmother, my mother, Mary Belle Jones Lewis (1923-2016) loved Uncle Howitt. His daughters, Priscilla and Laura Belle, were her favorite cousins and treasured life-long friends. Like me, Mom loved family history and collected many items that are now part of my genealogy collection. Mixed in with papers sent to her by Priscilla, I found a photocopy of a picture of Martha.

On the back of the photo of Martha, Uncle Howitt wrote, “I called her my ‘colored mamy’ as did rest of family and she was treated as one of us as long as she lived. She had her own room and own things which were furnished by my grandpa and grandma.”

The thought of this makes me feel uncomfortable. The way my family swept formerly enslaved people into their households as servants who worked without agency was not unusual for the time. Yet I still feel uneasy and awkward about how to reconcile this past, let alone do something about it. Although I wasn’t raised by a Black woman, I have friends and relatives my age (ahem, 65) who were. And there were plenty of people descended from those who were formerly enslaved who did the cleaning, cooking, and yard and farm work at our house in Gloucester and my grandparents’ home in Mathews. I have a history of white privilege that I have known for a long time, but like so many others, current events are calling me to look and think about racism anew.

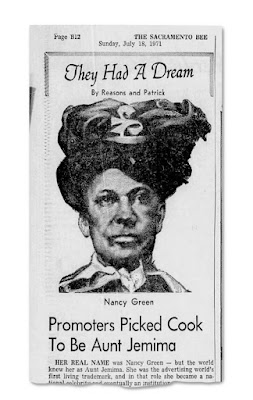

An article in the New York Times, Overlooked No More: Nancy Green, the ‘Real Aunt Jemima,’ says that the Aunt Jemima logo is an outgrowth of Old South plantation nostalgia and romance. This may have rung true at the time of the Columbia Exhibition, but thank goodness most people today aren’t nostalgic for a “Gone with the Wind” past. As my mother would say by way of explanation, “it was just the way things were.” Accept it and get over it. But what white people are waking up to now is that such things as a syrup brand and a statue of Robert E. Lee are legacy items from that “just the way things were” time. We cannot just get over it. They are hurtful to some and harmful to us all as we move our diverse society forward. Aunt Jemima was a brand. Nancy Green was a real person. She had a job, was a church missionary, had a family, and died in a car crash in 1923. The United Daughters of the Confederacy tried to erect a monument to “faithful colored mammies” on her grave, but the measure was not approved. Thank goodness. One less monument to tear down today.The New York Times article which gives agency to Nancy Green references an earlier article by Riche Richardson, an associate professor in the Africana Studies and Research Center at CornellUniversity. She writes that the Aunt Jemima logo is “grounded in an idea about the ‘mammy,’ a devoted and submissive servant who eagerly nurtured the children of her white master and mistress while neglecting her own. Visually, the plantation myth portrayed her as an asexual, plump black woman wearing a headscarf.”

Yes, just like Uncle Howitt’s Martha. In his inscription, he said that Martha was “a woman born into slavery” and who was owned by his 1st and my 3rd great grandparents, Thomas Richard Debnam (1806-1883) and Pricilla Macon (1812-1878). The 1860 US Federal Census Slave Schedule lists them as the enslavers of 52 people in Wake County, North Carolina. They gave Martha to their daughter, my 2nd great grandmother, Arabella Catherine Debnam (1837-1900), who married Alonzo Ross Hodge (1835-1910), in 1858 and lived at Marks Creek, Wake County, about ten miles east of Raleigh, North Carolina. Uncle Howitt wrote that Martha helped raise Alonzo and Arabella’s children: Alonzo Richard Hodge, Priscilla, Fannie, Aurelia, and Belle. “Martha outlived grandpa and grandma, although she had attacks of asthma when I was a small boy and then went to live with my uncle Alonzo Richard Hodge until she died in her late eighties.” In the 1870 US Federal Census, Martha is listed as a 35-year-old black domestic servant in the household of AR and Arabella Hodge.Martha died between 1920 and 1925. I don’t know if she had a husband or children. The only documentation credits her with no life of her own. I have walked around graveyards in Wake, Franklin, Granville, and Warren counties looking for ancestors. I never thought to look for Martha and I wonder if she’s buried with her white family.

Probably not.

Great research as usual. My grandfather Howitt spoke about Martha on several occasions. He was very fond of her and considered her to be a part of the family. He mentioned her influence on his medical career. She had severe asthma and he spent many nights caring for her—sitting up with her and even giving her morphene so she could relax and sleep. Yes the slavery thing was bad but here were some people doing their best in trying circumstances. They lived lives helping each other. My grandfather had nothing but affection and compassion for Martha. I am sure she was kind and loving to engender such feelings among those in her adopted family.

ReplyDelete