But perhaps the timing is right. These days I have the time and the will to confess my ancestors and, to paraphrase L.P. Hartley, process this foreign country that is my past.

After taking the sword home, I Googled until I decided it might be from the Civil War. By this time, my sister had found among my parents’ possessions some Confederate currency stashed between the pages of an old book. The plot had thickened. I gathered up a list of Confederate great grandfathers and took their records and the sword, which I didn’t know was actually a saber at the time, to my friend, J. Michael Moore, a Civil War historian.

Michael identified it as the kind of weapon a cavalryman used, while demonstrating how it might be wielded by a man on horseback. He thought the only one of my direct ancestors it could have belonged to was Walter Gabriel Jones (1837-1919). Because the saber had no makers' marks, Michael thought it was of the sort brought into the South from Europe by blockade runners. I was tempted to imagine that the saber was handed off to the young enlistee by my 3rd great grandfather Lewis Hudgins (1797-1866) who headed up a Mathews-based smuggling cartel that styled itself “the Arabs.”When he enlisted, great-grandfather Walter was 23 and lived with

his large family in the tall Federal-style house at North called “The Battery.”

The three-story house over a high English basement was built by his father,

Edmond Healy Jones (1798-1874), who came to Mathews from Middlesex and married

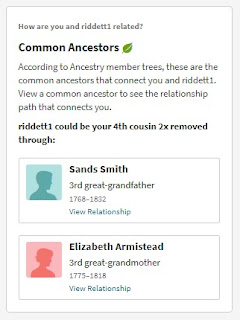

Harriet Smith (1809-1887) in 1827. Harriet’s brother was the locally renowned Sands Smith II (1803-1863).

By 1860, the year before the Civil War broke out, U.S. Census records say Edmond and Harriet Jones had seven sons and a daughter, ages seven to 30. The family lived on 337 acres and their real estate was valued at $10,000, or about $317,000 today. More than half of the property was wooded and 130 acres were “improved” or cultivated by the 15 people they enslaved. These people, whose names we will probably never know, lived in four cabins on the property. They grew wheat and corn, which were the most common crops grown in Mathews at that time. The Joneses also sold wood, possibly for shipbuilding.

Harriet’s older sister, Elizabeth Smith (1801-1870), got married a few years before her sister, in 1821. She married Robert Billups (1796-1872) and the Billupses and Joneses were neighbors on Blackwater Creek, a tributary of the North River. In 1860, they had two daughters and three sons, ages 19 to 28, living with them. Their oldest daughter, Sarah, had married Joshua Gayle, and the Gayles lived next door with five young children, ages two to 11. The Billupses' real estate (where the oldest son, Gaius, built Green Mansion in 1903) was valued at $20,000, or about $634,000 today. The 34 people they enslaved cultivated 320 of their 450 acres and were provided two cabins for all of them to live in, bunkhouse style.

On the other side of Mathews, Harriet’s brother, Sands, also lived on land valued at $10,000 in 1860. He and his wife had eight daughters, ages four to 24, and two sons, an infant and a nine-year-old. They enslaved 38 people who lived in four cabins on Smith’s plantation property called Beechland.

Another brother, Thomas Smith (1805-1880), lived near Sands at

Willow Grove, the house where the siblings’ parents had lived earlier. Harriet,

Elizabeth, Sands, and Thomas, as well as five more children of Sands Smith I

(1768-1832) and Elizabeth Armistead (1775-1818) were born there. Thomas had five

daughters, ages nine months to 24 years, and four sons, ages three to 20. His real

estate was also valued at $10,000. Thomas enslaved 54 people and provided five

cabins for their housing.

As a child, I never heard stories about the Civil War and slavery from family. A hundred years is a long time and most with first-hand knowledge were long gone, although I detected even then that some were sad or gruff for unknown reasons. I never knew about my maternal Jones family’s relation to the Smiths and the Billupses, either. However, what I did hear stories about was that the Joneses kept watch from the towering Battery’s attic windows for “enemies” coming from the lower Chesapeake Bay. As a child, I was unsure who those enemies might be, but it was an awesome and romantic tale.

What I’ve put together since is that the Jones-house-based watchers

were intent to aid their Smith family and friends on the other side of Mathews

during the Civil War. Confederate sympathizers all, they smuggled food, weapons, and supplies into the Chesapeake Bay and across from the Eastern

Shore. Smugglers tucked deep into Horn Harbor and other waterways. From Mathews’

docks, goods moved over land to wherever they were needed. Mathews was also the

source of direct food aid to the Confederacy, especially salt, milled grain,

and cattle.

What I’ve put together since is that the Jones-house-based watchers

were intent to aid their Smith family and friends on the other side of Mathews

during the Civil War. Confederate sympathizers all, they smuggled food, weapons, and supplies into the Chesapeake Bay and across from the Eastern

Shore. Smugglers tucked deep into Horn Harbor and other waterways. From Mathews’

docks, goods moved over land to wherever they were needed. Mathews was also the

source of direct food aid to the Confederacy, especially salt, milled grain,

and cattle.

Brothers Sands and Thomas Smith, like nearly everyone else in the county, were deeply sympathetic to and involved in smuggling activity. But the Union army was wise to them and determined to cut off the supply line through Mathews. This led to the deployment of 1,000 Federal troops and 11 gunboats, and a punishing counter-insurgent expedition known as Wister’s Raid.

Sixty-one-year-old Sands Smith, my second-great granduncle, is legendary for having shot a Union soldier and being dragged through Mathews in retaliation. He was then hanged, shot, and buried in a shallow grave as an example to other Mathews partisans. I don’t think this changed a single Mathews persons’ mind, though. They lionized Smith and dug their heels in further.My Jones, Smith, and Billups kin, like every person with a brain, had certain values at their core which were built and strengthened through life. They filtered new experiences through them and sprouted new brain wiring to support the core. They believed these learned and deeply rooted values, their way of life, prescribed the way things should be. Whether you believe in a cause for the Civil War that was right or wrong, this wired-in world view is why their young went to war. Their way of life was being challenged. You know, people just don’t like to be told what to do.

And their young men paid the price. In Mathews, the Confederacy’s first recruits, men ages 18 to 45, joined the Mathews Light Dragoons, F (3rd) Company, 5th Virginia Cavalry, on July 23, 1861. My great-grandfather was among them, as was his 28-year-old brother, Sands S. Jones (1833-1866), and his 20-year-old first cousin and next-door neighbor, Thomas G. Billups (1841-1886). Three more Jones brothers, Thomas (1829-1876), Lewis (1840-1904), and Christopher (1843-1919), and another first cousin and Thomas’s brother, Gaius W. Billups (1835-1920), also enlisted in the same cavalry unit by the summer of 1862. Of the Smiths, Sands had no sons of age to fight and Thomas had one, who joined an infantry unit, I believe (I haven't researched this fact thoroughly).

Of the four Smith siblings, Harriet, Elizabeth, Sands, and Thomas, my 2nd great grandmother, Harriet, had the most to grieve. Five sons left to fight for the Confederacy. Five sons! My heart aches and it brings me to tears to think about her living through all of this. The world was changing. Technological advances were making slavery less necessary, yet they couldn’t see a way forward. They couldn’t make their brains bypass the wiring that made them think their way of life was the way things were meant to be.

Of course, I never knew my great grandfather and his brothers. It would be interesting to interview them. Was war worth the costs? They certainly lost a lot. When my mother dug up a photo of my great grandparents Walter Gabriel Jones and Sarah Elizabeth Gayle, I remember my father saying they were “just poor dirt farmers,” or something of that sort. He didn’t know their history. Their world changed, a war was fought, they suffered, so it seems. Or perhaps not. Perhaps they were very happy with their lot. I will never know any more than what is intimated by the records I have found, and I share this below.

During the Civil War, 23-year-old Walter Jones fought in battles across Virginia for nearly two years until he was taken prisoner at Cold Harbor in the spring of 1864. At least he lived: of the 108,000 troops involved in the battle, nearly 15 percent lost their lives. It was also amazing that Walter survived yet another year at Point Lookout, a Union POW camp in Maryland, renowned as the worst and most crowded. According to the NationalPark Service website, Union prisons were filling up fast after the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863. Point Lookout’s POW population swelled from 1,700 to 9,000 in 1863. When Walter arrived in the summer of 1864, the prison population had grown to 15,500, well beyond the stockade’s capacity, and would reach 20,000 by the time all was said and done. Walter was “exchanged,” or sent back to his unit in exchange for Union POWs, on March 16, less than a month before the end of the war, on April 9, 1865. Prisoner exchanges were adopted during the Civil War to lessen the issues (overcrowding, lack of sanitation, disease) and costs associated with maintaining and moving captured soldiers.

Walter went home to Sarah Elizabeth Gayle (1844-1925), whom he had married in 1862, seemingly after his first year of battle and before reenlisting. After the war, on March 6, 1866, they welcomed their first child, Mollie. In 1868, Alice was born, and on March 4, 1870, Lewis was born. When 1870 census taker Owen stopped in, he recorded that the family was living in the Piankatank District of Mathews on 60 acres of land valued at $800, or about $16,000 today. They owned one horse, two milk cows, and a hog. During the previous year, they had grown 100 bushels of Indian corn and 50 bushels of oats.

[Interestingly—to me although not germane to this post—the next dwelling on the U.S. Census enumeration was occupied by paternal second great grandparents Absolom Forrest (1818-1871) and Columbia Ripley (b. 1836) and great grandfather Alpheons Lee “Allie” Forrest (1867-1949), then four years old. The Forrests lived on 11 acres valued at $300, or about $6,000 today.]

Thomas A. Jones (1829-1876), the oldest Jones brother, was 32 when he enlisted in August 1862. After a year and a half, he went AWOL (absent without leave) in November and December 1863. He had reasons to want to return to Mathews then: his mother, Harriet Smith, then in her 50s, had given birth to an eighth son, Henry C. Jones (1863-1946), her ninth and last child. Also, Mathews was the site of conflict from late summer into the fall. As mentioned above, Union troops were trying to halt Confederate smuggling operations and Sands Smith, Thomas’s uncle, was killed in October 1863. Despite the family emergency, Thomas was back with his unit in January 1864. In May 1864, he was one of 4,000 Confederate cavalrymen under General J.E.B. Stuart who met 12,000 Federal cavalrymen on their way to raid Richmond at Yellow Tavern. During the conflict that ensued, Stuart was shot and died the next day. Thomas was one of 300 cavalrymen who were captured and transferred to Fort Monroe in Hampton, then transferred to Point Lookout, Maryland. Although it was crowded, Thomas may have seen his brother there. Walter had been taken prisoner two weeks earlier. Thomas was transferred to the Union prison in Elmira, New York in August. Records say he escaped or was freed during a prisoner exchange, using an assumed name.After the war, Thomas returned to Mathews. The 1870 Census shows him occupied as a clerk and living with his parents, Edmond and Harriet Jones, and six siblings. War records list his death date as March 12, 1876, at the age of 46, just two years after the death of his father and 11 years before the death of his mother. He never married. The parents and son may be buried together at the Smith-Borum graveyard on Route 607 in Mathews, which served the homeplace at Willow Grove.

Sands S. Jones (1833-1866) was occupied as a seaman when he enlisted with Walter in July 1861. He was discharged from the cavalry unit for disability in June 1862. He died in 1866 at the age of 33. Unless a baby died in childbirth, which is entirely possible, Sands would be Edmond and Harriet’s first child to pass away. His place of burial is unknown, but it is likely he was buried in the family graveyard at Willow Grove with his martyred namesake uncle.

Lewis Robert Jones (1840-1904) enlisted in the 5th Virginia Cavalry with his brothers when he was about 21. He suffered a severe head wound in the Battle of the Wilderness, about a month before his brothers Walter and Thomas were taken as prisoners at Cold Harbor and Yellow Tavern. His situation after the war is unknown. A Civil War database says he died in King George County on May 3, 1904, and is buried in Mathews, although the location of his grave is also unknown. Since I suffered a head injury in a car crash when I was 21 and have studied neurology, I have an inkling of how his life may have unfolded. I have special empathy for him.

Christopher Muse Jones (1843-1919) was the youngest of the five Jones brothers who served in the 5th Virginia Cavalry. The Civil War database doesn’t give his age at enlistment, though he was possibly 18 or 19 years old, and there is no mention of him in available records of roll calls, battles, injury, or imprisonment. He is listed as living with his parents after the war, in the 1870 U.S. Census, but by the 1880 census he was living with his wife, Martha, and their three daughters in the Piankatank District of Mathews. The couple would have 11 children before he died in 1919.

After the Civil War, according to the 1870 census, Edmond and Harriet, ages 73 and 62, were living with Thomas (40), Christopher (23), “Doctor” (20), Mary E. (22), Ernest (17), and Henry (7). Their real estate was now valued at $7,000, or about $141,000 today, or half its worth ten years earlier. Walter was married and lived in the Piankatank District of Mathews. Sands was dead, and Lewis’s whereabouts are unknown. Between the Joneses and the next household of White people lived the Emancipated Black families of Daniel Parish, William Brown, Abraham Smith, and Charles Brucker. The Parish household included a 16-year-old girl named Sarah Jones.

After Harriet’s death in 1887, Walter and Sarah moved to the Battery with their ten children. The photo of Walter and Sarah that my father believed to represent “poor dirt farmers” must have been taken sometime before Walter’s death in 1919. Their son and my grandfather Roland Christopher Jones (1886-1963) married my grandmother, Laura Belle Foster (1890-1976) on October 21, 1915, and they moved into a house across North River Road from the Battery, where my mother was born.In the 1870 census enumeration, five households separated the Edmond Jones family from the brothers' first cousin and brother in arms, Thomas G. Billiups. In that year, he was 28 and a physician, living with his wife and children, ages one and three. His real estate was valued at $3,000, or about $60,000 today. His parents Robert (76) and Elizabeth (60) Billups, and sister, Roberta (26), live in the household, too.

If you are Black and you have read to the end of this post, you are certainly mocking the very idea that my family was sorely harmed by the Civil War. They were, but they weren’t. They didn’t know what it was like to suffer the pain and indignities of slavery, then a failed period of reconstruction and Jim Crow. And I don’t know what it’s like to live with systemic racism. I get it. I know.

No matter who you are, time marches on. We have history. We

learn lessons. How can a realistic look at our ancestors and their world help

us see each other more clearly? I am reminded of Tara Brach’s RAIN acronym. Rather

than continuing to believe that the way we see the world is the way it should

be, can we loosen our wiring long enough to recognize when we are being thrust

forward by impacted core beliefs? Can we accept that they are neither good nor

bad, that they are the result of time and experience? Can we investigate

how to get around being stuck in our worldview? Can we nurture a new path

forward?